Abstract

Using broad analyses of data for international study programs at Brigham Young University as well as a specific case study, we illustrate how the core concepts of service learning ‘experiences and involvement; mentoring and reflection; and linking service experiences with academic concepts’ are key to successful international academic experiences for students. By using data from over 1,200 student post-program evaluations, 16 faculty director interviews, and a specific case study on a service learning course in Southeast Asia, we illustrate the importance of closely mentored service-learning opportunities and rigorous academic expectations as keys to students’ self-assessed academic growth and over all satisfaction with their international experience. We conclude that well-developed international service learning programs create unique opportunities for students to become better world citizens.

Introduction

With the well-documented increase of U.S. college students who study abroad at some point during their college career, there have been concomitant attempts to analyze the effect of the international study experience on these students. However, documenting the effects is often complicated because ‘the most prized learning outcomes such as advanced critical thinking, oral communication, and written expression tend also to be the most difficult to measure empirically’ (Sutton and Rubin 2004: 66). In addition, the exact location and time where learning takes place may be difficult to pin down, and, although it is diminishing, there is often a presumption that learning will miraculously happen just because students are in an international location (Wilkinson 1995). Additionally, several studies have found that students grow in different ways while on study abroad (Cash 1993; Gmelch 1997; Ingraham and Peterson 2004). Understanding the specific practices that lead to this growth can be complicated.

This research combines statistical analyses of 1,234 post-program evaluations of students participating in international programs, interviews with 16 faculty directors for these student programs (representing those rated lowest, highest, and mid-range for academic growth), and a specific case study of a highly rated service learning program in Southeast Asia to illustrate how some of the key concepts for successful service learning are also key factors that influence academic growth on all international programs – whether centered on service or not. Close mentoring by faculty, effective courses, active student involvement in their surrounding communities, and reflection on connections between experiences and academic concepts are shown to be key to students’ academic growth and over all satisfaction with their international study experience as well as the foundation for the successful service learning program in Southeast Asia.

Brigham Young University (BYU) has been sending students to study internationally for decades, and currently sends over 1,000 students each year to study in international locations. There are four basic types of international programs at BYU:

- study abroad, which combines standard, university courses ‘usually taught in classrooms on a semi-regular schedule’ with travel and living experiences;

- internships, which focus on student work experiences in an international setting;

- field studies, which involve students in research projects in international settings; and

- service learning programs, which combine university coursework with service placements in an international setting.

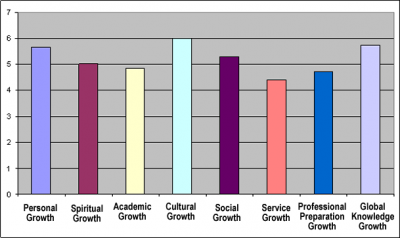

To better evaluate the experiences of students and assess the academic impact of these programs, a scale to measure the students’ perceived growth in a variety of areas was administered to all international study participants at BYU. At the end of their international experience, students were asked to rate their growth in the areas of personal, spiritual, academic, cultural, social, service, professional, and global knowledge. These categories of overall growth were identified and substantiated using a factor analysis employing a varimax rotation, which showed that they were all distinct measures of overall growth. Figure 1 below shows the mean ratings given by students who completed the assessment during 2003-2004, after participating in an international study program.

Figure 1: Student Growth on International Study Programs

Some of the differences in the types of growth experienced can be explained in part by the fact that not all programs focus on these specific concepts. (For example, internships would be expected to get higher ratings for professional growth and service learning programs to get higher ratings for service growth.) However, academic growth should be relevant and important for all types of programs. In attempting to understand which factors influence students’ level of academic growth, some interesting differences were found between students’ ratings for academic growth as compared with their overall satisfaction with their international experience. These differences are important because academic growth can be understood to represent the desired outcome for universities sponsoring international programs, while program satisfaction represents an important but more superficial aspect. For those closely connected with universities, the need to better understand and demonstrate the academic impact of international study is becoming ever more important, as budget constraints demand justification for the extra costs associated with international ventures. Consequently, we must better evaluate whether or not international study provides a unique learning venue for students.

Table 1 below compares the significant factors found to influence students’ academic growth with those influencing their overall program satisfaction. Numbers in parentheses represent the standardized coefficient for each factor, thus a bigger number signifies a greater influence.

Table 1:

Significant Factors for Academic Growth and Overall Program Satisfaction

| Academic Growth | Program Satisfaction |

| Course rating (.328) | Course rating (.247) |

| Informal discussions with professor as a learning tool (.211) | Informal discussions with professor as a learning tool (.156) |

| Credits count toward major, minor, or GE requirements (.174) | Satisfied with program administration (.145) |

| Preparation class is good use of time (.097) | Preparation class is good use of time (.124) |

| Amount of time student has spent outside of native country (.086) | Director showed genuine interest in student (.111) |

| Director is in field with program (.059 – approaching significance) | Money spent on souvenirs and gifts (.084) |

| Concerns about personal safety (-.084 negative factor) | |

| Amount of time student has spent outside of native country (-.082 negative factor) | |

| Student income (.080) |

Most significantly, income, personal safety, souvenirs, and program administration are not significant predictors of students’ self-assessment of academic growth. Rather, academic growth during an international experience is influenced primarily by the quality of the courses taught, student interactions with their professor (especially in informal settings), relevance of the classes to the students’ interests and major, and the experiences students bring with them. These findings support the foundations of service learning:

Service-learning is an instructional methodology built upon a foundation of experiential learning enhanced by critical, reflective thinking. Through community service, participants have opportunities to enhance their civic and social responsibilities and to develop critical-thinking and group problem-solving competencies (Norbeck, Connolly, and Koerner 1998).

While not all international study programs at BYU incorporate service, our research found that the foundations of service learning experiences and involvement; mentoring and reflection; and linking experiences with academic concepts were also the key factors contributing to increased academic growth on all international programs. Those programs that combined international experiences with strong mentoring by faculty directors and rigorous courses where students were able to reflect on and process their experiences were rated highest for academic growth by the students who participated in them. Service placements, while not always used by these programs, are one of the most dependable ways to facilitate student experiences with real people and issues in their international setting.

International study programs also put professors and students in close contact with each other in settings outside of the formal class room. When such contexts are used to mentor students, the learning experience is greatly enhanced. As Vande Berg et al assert, ‘more students now return to their home campuses sharing stories about their experiences with many stories focusing on the extraordinary things the students report experiencing outsidethe academic setting’ (2004, 103).

When there is a faculty mentor present, students may experience more than just ‘extraordinary’ events during their international study, they may experience a way to interpret such events. Thus the learning is tied to experiences outside of the formal classroom but maintains the interpretive role of the professor. Service learning programs can be especially productive in this international context. The service component of the program puts students in a position to have more direct, real experiences in the international setting as they interact with real people and real situations in their service placements. In international contexts, service learning as a strategy is designed to support and capitalize on the very factors that support academic growth – sound courses; requirements to work, interact, and contribute to the communities where they are studying; reflection on and analysis of key concepts both in the courses and volunteer venues in close partnership with their professor; and helping students connect their own experiences, frustrations, discoveries, and viewpoints with academic concepts to make their international experiences relevant to them personally. The data from BYU international study students clearly show that programs that facilitate these types of connections are the most successful programs in promoting student academic growth.

In an effort to more clearly explicate these connections, one of the authors also conducted in-depth semi-structured interviews with 16 faculty directors of international programs (comprising over 340 students) at BYU. The 16 directors were chosen to represent a range of programs based on student evaluations concerning academic growth. One theme that immerged consistently across the interviews is that the highest-rated programs had strong mentoring components. The following comments from both students (extracted from post-course evaluations) and faculty (extracted from the in-depth interviews) show the importance of mentored learning and the unique opportunity that international study programs provide for it.

I couldn’t have asked for a better director. It was obvious to all of us that he was passionate about what we were learning, and he thus instilled a love of art in each of us. He was ever concerned for our welfare and yet allowed us to be adults at the same time and didn’t baby us. I felt his confidence and trust, which enhanced my confidence in myself and allowed me to grow personally. He was also very spiritually inspiring. (Student, Art History-Europe)The biggest thing is that I have a relationship with those 26 students – the relationship that I have with the other students that were down there is a closer relationship than I’ve ever had with students before – and I do mentoring research [here on campus] where I take them out in the wilderness. And that’s the benefit – That puts you in a different situation teaching. One of those students is in an academic class that I teach now. I think she sees me in a way that’s different from the other students. It’s a difficult, rigorous class, and students get discouraged. I think because she’s been with me and knows me that that relationship really helps her in the class, and it’s good. (Professor, Health and Human Performance)

[Students will] never forget [what they learned on this program] because they found it. My lectures are such that they lay the trail for students to learn from their own experiences. And I use their experiences as part of the bread crumb trail. So experiences aren’t just abstract stories. Experiences are more universal. They experienced the same things you did, at least to an extent. In a class here [on campus], I’m telling stories, and I’m asking others in the class to tell stories to make the concepts. [On the international program] we all have the same experience, maybe a little different story off of it, but everyone’s relating to the same shared experience [and it becomes] a catalyst. They had to literally apply the concepts to what they were experiencing at that point and time, so they couldn’t fake it. There were nights when the lights in [the students’] apartments were on very late. And it was a delicate balance. I’ll just argue that it was not so much different [from learning on campus], other than it was brought down to a more concrete level, less abstract. The learning happens quicker because of two things. You’re all having the same venue where you’re experiencing stuff. You might experience it different, but you’re all having the same venue where you can make stories off of it. You can swap stories. The other element of it is that you can render the ineffable effable. You can take concepts and plug them into real, concrete situations right now, and you can talk about it that week. (Director Southeast Asia Volunteers)

Both the survey data and the qualitative interview data point toward mentored learning as a key to academic growth on international programs. However, in addition to mentoring, rigorous courses and connecting experiences to learning were also found to be important influences on academic growth. While most of the students and faculty directors surveyed and interviewed were not directly involved in service learning, the highest rated program for academic growth was a service learning program – the Southeast Asia Volunteers program. This program demonstrates the important contribution that service learning can make to academic growth on an international program. Because the influences identified as key for strong academic growth by both the survey and faculty interviews form the foundation for service learning, a well-executed service learning program has great potential to inspire students to greater academic growth. There are many factors that influence student academic growth. For example we found that the caliber of students- not just GPA but personality, past international experience, and major – has a great influence on the overall program and whether students will perceive that they have grown academically. Group dynamics, the difficulty of the courses and assignments, the disciplinary focus of the program, and many other factors such as native vs. home campus instructors also figure in. So, we would not argue that every international service learning program will provide students with great academic growth. However, if well executed, service learning programs have the potential to bring in the most important ingredients to help students grow academically from their international experiences. As one of the most successful service learning programs at BYU, a case study of the Southeast Asia program will provide an example of how the many important concepts of service learning came together successfully so that students felt they made great progress academically. Three of the authors of this paper represent the faculty director and the two student facilitators for this program.

Case Study in Thailand/Southeast Asia

The Southeast Asian Volunteers program mixes demanding academics with 20 hours of service a week in three different service venues in Chiang Mai, Thailand, creating a mosaic of academic enrichment, volunteer experiences, and research and internship opportunities. The faculty director lives in country for the three months the students are there and makes himself easily available for both formal and informal discussions with students.

The program is open major, thus participating students come from a variety of majors, and is basically structured along the following five components:

- Both a preparation course and Thai 101 courses are required the semester before leaving for Southeast Asia;

- Students can chose from three official service venues for their 20 hours. These include teaching English to children in two different Hilltribe schools in Chiang Mai, helping with children in a local orphanage, and working on an organic mango farm sponsored by the King of Thailand as one of his economic development projects. Students may also design their own service venue with the approval of the faculty director;

- An extended 2 to 3 week ‘excursion’ to other areas within Southeast Asia including, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Cambodia;

- More locally-based weekend cultural field trips; and

- Completion of three courses in country: Southeast Asian Religions and Culture; Globalization and Social Change in Southeast Asia; and a service internship from the student’s major, designed by the students and an appropriate faculty advisor.

Using observational data and comments from course evaluations gathered over the past two years, we illustrate the general structure of our program and some of the academic growth and personal changes that students experience through it.

Students are carefully chosen for this program through a rigorous application process. The process is designed to weed out potentially problematic students. The primary goal is to create a group that can be both supportive of each other while also challenging each other to achieve. We are seeking students who will be actively involved in and committed to both the volunteer and academic portions of the program.

Winter Preparation Course

The main goals of the preparation course are to help set realistic expectations, start students on the academic journey that will continue throughout the program, and give them some basic cultural and language skills. Before leaving for Thailand, students accepted into the program attend a preparation course during winter semester as well as a Thai 101 course. The majority of the students who participate have not spent significant time in a foreign country, consequently, the preparation and Thai 101 courses help students transition into the Thai culture and language while hopefully minimizing the effects of culture shock.

The prep course is divided into two parts. The student facilitators teach one half of the class focusing on culture, norms, program logistics, and language skills. The other half of the class is taught by the faculty director. In an attempt to prepare the students academically, approximately one third of the 15 books (ranging from topics on the Khmer Rouge, Vietnam War, Globalization, Buddhism, Islam, Sikhism, etc.) for the courses taught in Thailand are assigned and read during the winter prep course. The faculty director’s lectures focus on Southeast Asian history, colonialism, and contemporary social problems. This insures that the students are well prepared academically for other than a ‘tourist experience’ when they arrive in Southeast Asia. It also allows a considerable amount of academic rigor without forcing the students to constantly have their heads in the books during their stay in Southeast Asia. Front-loading the program with readings and lectures before departure is intended to give the students different tools by which to interpret their experience in Asia. That it generally accomplishes this is illustrated by the following comments made by one of the students in their course evaluation:

Boy, did this summer affect my life – understatement of the year!! One particular aspect of the program that I loved was learning about Southeast Asian religions, and being able to see those religions, especially Buddhism, first hand. It was walking in their temples, sitting down with them to eat, interacting with them on the streets that made learning about other religions real. In addition to [the director’s] great lectures, and our class readings, we were able to sit down with Buddhist monks and learn what they are all about, and what they believe. I was able to see the goodness in what they believed, whereas before, I simply knew nothing about it. Learning and interacting daily with people of other religions in Thailand opened my mind and heart to these people, gave me a greater understanding, appreciation, and respect for them and what they believe, and also expanded my understanding, and strengthened what I already believe to be true.

The prep course also served as a venue where students could ask more generic questions concerning Thailand and Southeast Asia. We found that many students with no international experience were prone to think that Thailand is ‘primitive,’ a place where people walk barefoot on dirt streets, etc. Consequently, they are surprised to learn that Thailand has modern toilets! Most students simply do not know what to expect in Thailand. During the prep course, they often imbued their concepts of Thailand and Southeast Asia with an exoticness that was counter productive, creating a feeling that it had to be so different from what they were used to that actually understanding the people and culture would be impossible. We worked hard to down-play this ‘exotic’ image. As one student commented:

At first when we arrived here [Thailand], I was a little shocked at how advanced Thailand really is. When I decided to volunteer on the farm, I was relieved at the drive out to the countryside, because it was how I pictured Thailand to be. In a sense, I expected Thailand to be all farm land and rice fields, but I was wrong.

Upon their arrival in country, students tended to be overwhelmed and excited about the differences in Thai and American culture to the point that all students seemed to perceive that there were differences. Yet over time these opinions shift rather dramatically to a feeling that Thai culture was the same as Western culture and finally to an ability to see and appreciate the differences in Thai culture as opposed to Western culture. The service placements are key in these transitions, as students become involved in daily life and real situations in Thailand rather than just seeing things from an outside perspective. All the time spent in the preparation class cannot accomplish what the real life involvement of the service placements does.

Thailand

The formal program runs from the end of April to the end of July. Students are encouraged to arrive at least two weeks early and leave two weeks after the official program begins and ends. This allows them an opportunity to see and experience the area before being tied to a more formal schedule. Once the program begins, the students’ weekly schedule consists of working at their service venues on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday until early afternoon, leaving their evenings generally free; classes on Thursdays until late afternoon; and Friday and/or Saturday a cultural field trip and the other day free time. Sunday is also a free day. Towards the end of the program the students also take an extended 2-3 week excursion throughout Southeast Asia. This program maintains a balance of service, lecture, and sight seeing conducive for learning and mind stretching experiences.

Students’ first few weeks in Thailand are generally spent trying to make sense of their own culture shock. This is most often evident relating to punctuality. Thai culture has a very flexible understanding of time. As students travel together, often they find themselves waiting on a taxi driver or other students and arguments about time management inevitably emerge.

Once in country, service placements, field trips and other less formal settings provide opportunities for the faculty director and student interaction outside of the class room. Indeed, countless hours were spent by the faculty director interacting with the students in these less formal settings. At the end of the program, several students commented to the director that one of the things they appreciated most was the ability to ‘pick the brain’ of the director. In an interesting twist, over the past two years, students from other universities on their own study abroad programs in the area ended up tagging along with our program because the director was so accessible. In particular, a group of four students from a Canadian university ostensibly joined the BYU group for some of the lectures and many of the field trips because they felt they were getting so much more out of the interaction. This type of interaction is one of the key factors that stood out in the survey of all international study students. The variable for informal discussions with a faculty member was the most important influence on a student’s perception of academic growth next to the actual courses on a program. Through both the survey and interviews with directors of the five programs rated highest for academic growth, we found that having the director or main instructor available to students both in and out of class for questions and discussions was vital to the programs’ success. All five of the top programs had faculty who made extra efforts to be available to students outside of class to discuss both academic and non-academic subjects.

The Southeast Asia program also focuses heavily on field trips and activities which coincide with the material the students are reading. Again, this emphasis aligns with findings from the student survey, where the learning opportunities identified by students as most important were daily living, informal interactions outside of the classroom that allowed them to experience the international setting for themselves. Field trips, living with host families, and interacting with locals were identified by more students as important learning tools than coursework, class discussions or readings. One of the Southeast Asia student facilitators remembered the first year that he took students to the war museum in Vietnam:

We spent about 3 hours at the museum. Afterwards, I could remember coming out and seeing all the students sitting on benches with solemn expressions. Many of the girls in the group had tears streaking down their faces. After they boarded the tour bus to head back to the hotel, no one said a word. I think that experience helped remove the padded distance between fairy-tale and reality for the students.

Another student commented:

I think that our excursions complemented the courses very well, for there is really no way to describe how diverse Southeast Asia is and how each country has been affected by globalization differently without actually visiting some of the countries and seeing it for yourself. Going to the war museum and visiting the countryside in Vietnam brought a harsh reality to me about how much we are not taught, especially with a war that we didn’t win like the Vietnam war. Seeing how the affects of the war in Vietnam were still visible, and the feelings that I had when looking into the eyes of the older population and realizing how many loved ones they had probably lost in the war made me realize how repetitive history is. I thought about how one day I might be walking into a similar museum on the war in Iraq and once again be appalled at the things that went on.

The group also traveled to Cambodia and visited the killing fields, Angkor Wat and the S-21 torture prison in Phnom Penh. Seeing and experiencing these different places after reading and learning about them had a sobering impact on the students. During the past two years the program has also allowed students the opportunity to view and study different world religions and expose them to different ideas including Buddhism, Islam, Sikhism, Taoism, Hinduism, and many others. One student commented:

At the Hindu temple, I saw a man sitting in meditation, and I considered that he prayed to his God with the same devotion and faith that I prayed to my God with. I realized that he respected this place as much as I respect my [religious institution] in America. Perhaps this Hindu business wasn’t so different from my [own religion].

We have found that at the beginning of the program many of the students’ opinions concerning other religions tend to be very narrow and biased. This is especially the case with Islam. Compounding prior beliefs with the events of 9/11, many students viewed Muslims as evil and savage. However after studying about their beliefs, reading exerts from the Koran and traveling to Malaysia and making new friends there, many students acknowledged they had made changes to some of their core beliefs. One student shared:

Most of my life, I have understood that being American and [worshipping in my religion did] not make me better than everyone else in the world. However, it wasn’t until I treaded past the faces at the Malay market that I began to believe it. These were real people with real feelings. And they had something real to offer me in my life.

The students’ participation in the service venues was especially important in helping them be able to take an interest in and comprehend new perceptions of both personal and academic subjects. One of the facilitators commented on this:

I remember one particular experience when some of the other students and I were working on an agricultural development project in northern Thailand. In particular, we were weeding a Mango orchard in Chiang Mai Thailand. I remember one particular day that really stuck out in my mind. The students and I were in the hot sun weeding two to three foot weeds with sweat pouring off of us. We were using hoes and rakes to weed around the mango trees. After a few hours of weeding in the hot sun, we noticed a Toyota van pull down the dirt road to the farm and park. A bunch of Cambodian tourists piled out of the van, and the owner of the orchard met with them and started showing them the orchard and giving details on his agricultural project. Some of them spoke a little Thai, and so I went up to a few of them and started talking to them. Many of them were surprised after they learned that this group of students from America was here in Thailand working in the hot sun without any real return investment. It was a neat experience because we were providing a new image to these Cambodians of Americans.

Not only were the students learning that there were more similarities between themselves and other Southeast Asian cultures and people, but the people with whom they interacted also began to make these same opinion shifts of Americans. One student made the astute comment that: ‘I went to Southeast Asia expecting to discover the differences between my world and their world. Yet, the more I search, the more similarities I find within our worlds.’

Such comments became more common toward the end of the program. The combination of readings, lectures and discussions, volunteer work, and excursions to different religious and cultural sights formed the basis for many of these changes observed in the students. One student summed up many of the issues discussed above:

I think that seeing how people really live their lives every day has really given me a different perspective than if we were only to spend even a couple weeks in one place. Because we’ve been in Chiang Mai for so long, and we have a regular and productive schedule, we are able to actually form relationships with people – something a tourist simply doesn’t have the time to do. I don’t think that coming here has given me any answers, and if it has, these answers have only led to bigger and more complex questions. But these questions keep getting more interesting because I see things differently now, and my curiosity grows exponentially. I am finding out for myself how to deal with the world and with life’s many paradoxes. Sometimes it’s easier to go through life without thought to the rest of the world’s terrible poverty, lack of education, and the many other hardships that many people endure every day without knowing any different, but once you’ve seen this you can’t go back.

The service learning venues of the program provided the most important and consistent opportunities for the students to engage the real world of Thailand along with the academic concepts they were learning. Through having prior academic preparation on culture, religions, and social problems, plus having a faculty mentor present, the students were able to interpret their experiences during the service venues in ways that helped them process and synthesize academic concepts and personal paradigms. Many of the lessons learned came through the personal interactions with Thai’s while serving. The service learning helped strip away some of the false pretenses and arrogances that Americans tend to have about the world. Friendships were built between the students and Thai’s. These friendships helped humble the students and allowed them to start seeing the Thai people and culture from their perspective instead of an ethnocentric one. This is self evident in some of the following comments by students:

When I first began planning to come to Southeast Asia, I thought very little of what I would learn from the service portion of our program. I was excited to go to Southeast Asia and learn from the people, to experience the culture firsthand. What I have found since I have been here is that some of my most rewarding time has been spent being engaged in service learning. For my service venue I have been involved with about 30 monks at a large Buddhist Wat in Chiang Mai. I spent around 15 hours a week teaching them English, and they in turn, teach me about Buddhism for close to five hours a week. It has been frustrating at times. I have come face to face with people and ideas that I don’t necessarily agree with at times, but because of these differences I have learned to respect people more for all the good they have inside them. I learn so much as I try to teach them. Watching the monks interact together and with me has given me insights into modern Buddhism that I would have never known otherwise. Reading about facts in a book is one thing, visiting sites is another, but the most helpful exposure I’ve had to culture and religion here in Asia has come with the time I’ve spent learning with and from the people.

The students we taught English to at the Hilltribe school were so enthusiastic to learn. The students did not just have enthusiasm for learning but for life. They were always looking to play games, make jokes, or sing songs. The students’ happiness always rubbed off on me, and I couldn’t help but smile throughout the class period. I also learned to be patient and easy-going while with them. As teachers, we had a teaching schedule for every day. However, the classes were rarely ready for us at the scheduled times. Usually, one student in the class would see us coming and take the next ten minutes rounding up the rest of the class. It was also difficult dealing with a language barrier, but I learned quickly that it was not worth it to get upset or discouraged. Instead, I tried to adopt the attitude of the Hilltribe school teachers of being laid back and relaxed. I discovered that my way of doing things was not always the right way of doing things.

Conclusion

The Southeast Asian Volunteer program at BYU has been successful because it combines close mentoring with required service placements, rigorous academics, and on-site experiences that simply cannot be had in a class room. By building off of service learning precepts, it also fit the larger pattern for academic growth found in the data from student evaluations as well as interviews with faculty directors. Based on interviews with multiple faculty directors of both successful and less successful international programs and multiple years of conducting the Southeast Asia program, we know that it takes a combination of academic rigor, the right opportunities for student involvement, a combination of high expectations and high faculty support and involvement with students, and the right types of students with the right motivations and expectations to produce an international program that will truly impact students – academically, socially, and culturally. We can’t deny that it also requires a bit of good luck. But international service learning programs have the right ingredients to produce a dramatic and unique academic impact on students by providing them with a consistent forum for involvement in their local communities, an academic framework for understanding their experiences, and enough informal interaction with their professor that they can process things in a relaxed and spontaneous manner. Most importantly, students find real-world applications to their learning and find their lives changed as a result. Such programs have the potential to produce not just better local citizens, but better world citizens.

References:

Gmelch, George. 1997. Crossing cultures: Student travel and personal development. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 21(4): 475-490.

Cash, R. William. 1993. Assessment of study-abroad programs using surveys of student participants. Paper presented at the Annual Forum of the Association for Institutional Research, Chicago, IL May 16-19, 1993.

Sutton, Richard C. and Donald L. Rubin. 2004. The GLOSSARI Project: Initial Findings from a System-Wide Research Initiative on Study Abroad Learning Outcomes. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study AbroadFall 2004: 65-82.

Ingraham, Edward C. and Debra L. Peterson. 2004. Assessing the impact of study abroad on student learning at Michigan State University. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad Fall 2004: 83-100.

Norbeck, Jane S., Charlene Charlene Connolly, and JoEllen Koerner, eds. 1998. Caring and Community: Concepts and Models for Service-Learning in Nursing. Washington, D.C.: American Association for Higher Education.

Vande Berg, Michael J., Al Balkcum, Mark Scheid, and Brian J. Whalen. 2004. The Georgetown University Consortium Project: A report at the halfway mark. Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad Fall 2004: 101-116.

Wilkinson, S. 1995. Foreign Language Conversation and the Study Abroad Transition: A Case Study. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Pennsylvania State University.

About the Authors:

Marie Bradshaw Durrant has a PhD in Sociology with research interests in how academic learning and international experiences are integrated as well as international study program evaluation. She was a research fellow at the Kennedy Center for International Studies at Brigham Young University with a specialty in service learning programs. She is now an independent consultant. You can reach Dr. Bradshaw Durrant at Marie Bradshaw Durant, 624 SWKT, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT 84602, 801/491-8246, or email marie_durrant@comcast.net.

Ralph B. Brown is a professor of sociology at Brigham Young University with research and teaching interests in community development and rural and international development. He speaks Indonesian fluently and is conversant in Thai. You can reach Ralph B. Brown at 2034 JFSB Department of Sociology, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602, 801/422-3242, or email him at Ralph_Brown@byu.edu.

John W. Bevell recently graduated from Brigham Young University with a major in Sociology. For the past two years, he worked as an undergraduate student facilitator for the Southeast Asia Volunteer program. You can reach John W. Bevell at Southeast Asia Volunteer, 2008 JFSB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602, 801/422-3242, or email him at johnboy101@gmail.com

Jacob B. Cluff is an undergraduate student at Brigham Young University studying sociology with an emphasis in research and analysis with two minors in Asian Studies and International Development. He speaks fluent Thai and has been a Southeast Asian volunteer program facilitator for the past three years. You can reach Jacob B. Cluff at Southeast Asia Volunteer, 2008 JFSB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602, 801/422-3242, or email him at jakecluff@gmail.com