Abstract

Human services education has an extensive history of using field-based, experiential learning to connect theoretical concepts with practice. The Council for Standards in Human Services Education requires a minimum number of hours of internship for different level programs (180 hours for the technical level, 250 hours for the associate’s level, and 350 hours of internship for bachelor’s level programs) with students linking their field experience with prior course content through field experience seminars. Such a requirement would seem to make human services a natural discipline for including service learning as a part of its curriculum.

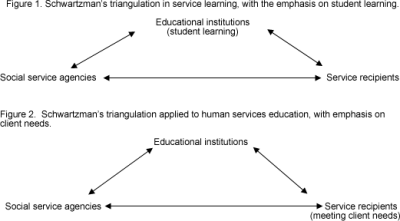

Schwartzman (2007) describes service learning as a triangulation of partners in an educational enterprise that links educational institutions and their students with community service organizations in order to provide some type of service to an identified clientele. This arrangement closely parallels what occurs in human service internships; an educational institution that offers a major in human services negotiates with local social service agencies for its students to have an opportunity to develop their skills experientially by serving clients, typically under clear and close supervision. Since these two processes so closely resemble each other, what can be gained by incorporating service learning into a human services curriculum? Can human services education and service learning complement each other? This paper addresses the value that can be added by blending the principles and value domains of human services education and service learning.

Human services, like other helping professions such as social work and counseling, is based on a set of values and ethics that address how human services workers should treat clients. These values are typically presented to students in introductory courses and infused throughout the remainder of the human services curriculum. While the identified values may differ slightly from text to text, a typical listing would include acceptance, valuing difference, client self-determination, and confidentiality (Woodside & McClam, 2006; Brill & Levine, 2005). Acceptance is similar to Rogers’ (1958) concept of unconditional positive regard; every person is to be valued as a unique individual, regardless of differences between the client and the helper. Such differences are not merely to be tolerated or accepted, but the human services worker endorses and supports diversity in all of its manifestations within the human community. Client self-determination holds that the client is the expert of his or her life, not the worker, and that he or she makes decisions about how it should be lived. The worker’s task is to help the client explore how decisions might turn out, not to act in hierarchical ways that reduce the decision-making capacity of clients. Confidentiality is linked to acceptance; a worker will not treat the information shared by a client in a cavalier manner. The worker will, to the extent possible, keep information the client shares as a private trust, divulging it only to supervisors or others with a clear need for such information. Each of these values implies that the core concern is to treat people with respect and dignity, regardless of social standing or the problems in their lives.

The benefits of service learning as a pedagogy have been widely accepted in U.S. higher education (Astin & Sax, 1998; Eyler & Giles, 1999; Eyler, Giles, Stenson, & Gray, 2001; Westheimer & Kahne, 2002). Astin and Sax (1998) found that students involved in service learning were more involved in civic engagement, performed better academically, and felt better prepared for leadership opportunities and their future careers. Schulze & Witt (2004) also found that students involved in service learning developed a greater passion for civic engagement and a clearer sense of direction for their lives. Such findings have helped service learning become an established part of college and university cultures.

It is widely recognized that values and values education are an inherent part of service learning experiences. In an early work, Macy (1994) noted that service learning did not prescribe solutions for values education that transcend all people, but instead provides individual students the opportunity to address diverse questions of moral importance within themselves and society. As a developing pedagogy, a universally accepted set of values does not yet exist for service learning. Chapdelaine, Ruiz, Warchal, and Wells (2005) have suggested that a code of ethics should be defined for service learning, similar to that found in the helping professions, that reflects its values of justice, fairness and equality. Campus Compact’s Service Learning Toolkit (2003) lists some of the varied definitions and principles of service learning proposed by practitioners that identify important values such as student personal growth and development, reflection on experiences and academic learning, community partnership, collaborative work, empowerment and reciprocity.

While universally accepted values continue to be debated, three commonly identified principles guide the use of service learning: civic responsibility, reciprocity, and reflection. First, service learning acknowledges the value of civic responsibility. The importance of training service learning students in the principles of responsible democratic citizenship has been common in the literature (Battistoni, 1997; Boyer, 1994; Boyte, 2004; Chapdelaine, et. al., 2005; Colby, Ehrlich, Beaumont, & Stephens, 2003; Harkavy, 2004; Westheimer and Kahne, 2002). Harkavy (2004) asserted that “service learning best accomplishes its goals by engaging students in collaborative, action-oriented, reflective, real-world problem solving designed to develop the knowledge and related practice necessary for an optimally democratic society” (4).

A second value base of service learning is the concept of reciprocity. In Schwartzman’s idea of triangulation, the relationship between the academic institution and the community partner or host agency must be based on reciprocity. While the students learn from the experience, the agencies and their service recipients must also benefit in some way. For example, Schulze and Witt (2004) suggest that part of this reciprocity involves the agencies receiving free labor from the students. Others have noted that this labor is not free; students often require training and orientation prior to involvement with the work of the agency, tasks that take the time of agency employees. Reciprocal community partnerships provide resources to all involved – community, faculty, students, and the educational institution – in a time when resources are limited (Trani, 2008; Ersing, Jetson, Jones & Keller, 2007). As service learning matures as a pedagogy, the value of reciprocity for all parties involved is receiving closer attention (Creighton, 2008; Miron & Moely, 2006; Sandy & Holland, 2006).

Reflection, the third value principle, involves students gaining new perspectives on their experiences, analyzing their behavior, emotions, insights and helping them to express what they are learning (Ash & Clayton, 2004; Fiddler & Marienau, 2008; Kiser, 2009; Kiser, 1998; Livney, 2008). “Reflection upon service is particularly beneficial in raising students to a new level of moral reasoning and development. They begin to identify issues in society, develop a greater understanding of these issues, and move to act upon them. Reflection is a process that allows students to clarify their own beliefs and values and begin to live consistently with them” (Macy, 1994, 67). The “learning” part of service learning only comes through intentional, purposive reflection.

While the three principles identified above are central to service learning, other ethical considerations may be derived from them. As a teaching tool, service learning contributes to the development of ethical principles. Chapdelaine, et. al. (2005) suggest these ethical principles include beneficence, nonmaleficence, justice, fairness, equity, fidelity, responsibility, autonomy, respect for peoples’ rights, integrity, and a sense of responsibility to be a knowledgeable and active citizen (16). While these concepts are similar to the key tenets of human services, their focus is somewhat different. In human services, the agencies and students are mainly focused on the lives and needs of service recipients. In service learning, the focus of the experience with agencies and service recipients is to provide assistance to the community agency and to the development of the students. This difference, while subtle, may create confusion or give students mixed messages when service learning is utilized within human services education. This is illustrated in the following figures:

Case Example #1

Students in an Introduction to Human Services course were required to complete forty hours of service at local social service agencies as part of the course requirements. Since the time commitment to service and the accompanying time for reflection met university guidelines, it was designated a service learning course. While many students took the course as the introductory course for the human services major, others took the course because of its service learning designation.

Four students in the class decided to do their service at an after-school program at a local agency that served youth from low income families. The white students, who came from middle and upper middle class backgrounds, initially felt they did not have much in common beyond having experienced childhood with the children in the program, who were mostly Black and Latino. The students’ responsibilities at the agency were to help children with homework after school and then engage in various recreational activities with them until their parents picked them up.

One month into the placement, the students came to class agitated over an incident they had observed. Two children had gotten into a “nasty” yelling match, hurling insults and threats back and forth, posturing with clenched fists. Apparently much of what they said involved racial slurs and promises of physical harm. While several of the university students tried to intervene and help the children cool off, the paid staff of the center did nothing, observing the altercation from the other side of the playground. The university students were furious, labeling the center staff as lazy, uncaring, and unprofessional.

From the human services perspective, the ethical issues being raised involved the treatment of the clients, the children at the youth program. The students were concerned with the staff attitudes towards the children they were serving. Issues regarding acceptance and valuing each child were seemingly being violated. The students also were concerned about confidentiality, not being sure if they had the right to share the identity of the children they had observed. At its core, the students’ anger and concerns focused on how the staff was not acting “professionally” in their treatment of the children at the center.

From the service learning perspective, the students were also concerned about their civic responsibility in the situation. Was it their job to address what they perceived as an injustice? To whom should they raise their concerns? What would happen to the staff if the students somehow got them in trouble with their supervisors? These and other questions focused on being responsible citizens and looking out for the well-being of others.

Processing the situation with the students involved the service learning value of reflection and the human services perspective of respect for the dignity of all people. The emphasis of the two approaches, however, was very different. From the human services focus, the emphasis was on what the students were learning about their expectations of service delivery systems, how they perceived clients, the roles of staff and supervisory relationships, cultural impacts on services, and the goals of social services. From the service learning side, the focus was on the students themselves; how their life differed from that of the clients, how they defined appropriate treatment of children, and what they could do to ensure children everywhere had opportunities to be treated in just and healthy ways.

Case Example #2

The Call to Service course was designed as a three-week immersion service learning course focused on homelessness. The class members were all first-year students who had applied for and were chosen to live in the Service Learning Community (a living-learning community) during their first year of college. They were drawn to the community for different reasons. Some had been involved in service during high school and wanted to continue, some were looking for a cohort group to make adaptation to college easier. All of them believed they were there to do something good and looked forward to serving others. For the most part, they were undeclared majors.

During the Call to Service course, students met in class to learn about homelessness, worked in local community agencies, and then traveled to Washington DC to work in similar organizations there. They learned about the structural causes of homelessness, the public attitude towards people who are homeless, the needs of homeless people, and actions for ameliorating homelessness.

Majors from the Department of Human Services Studies were used as student leaders in this course. The Human Services majors received course credit for their leadership work and were also given academic assignments. They were responsible for planning the service portion of the course, contacting agencies, making travel and lodging arrangements, planning meals, helping to keep track of the money, and other similar tasks. These students also co-led reflection sessions and served as mentors in the learning process.

Although the first-year students came to the course at a different developmental and knowledge level than the student leaders, there was a clear difference in the focus of learning that took place. The Call to Service students focused on learning about their own place in the world, how their lives fit with and affect those of the people who are homeless. They wondered about their own economic security, what caused people to be homeless and whether they themselves were at risk of becoming homeless. The first-year students were exposed to a new social reality in the capital of the United States and raised important questions about the contradictions they perceived. They saw monuments to people who gave their lives for the quality of life we live and also saw veterans without a home, families struggling to survive, and single men who have lost their dreams and visions. The service learning students returned to campus motivated to tell others and organize to implement an action strategy they had learned. Their experience clearly focused on learning about themselves and what they could do in the world.

The Human Services student leaders were impressed by these sights and thoughts too, but their focus was different. They were thinking more specifically about how their work affected the client, service delivery, and agency operations. For example, while the first-year students were reflecting on how easy it was to talk to the homeless people they met at a soup kitchen, the leaders were discussing what additional services were needed to move beyond meeting the need for a meal and truly changing the conditions that made such a need exist. Student leaders compared service delivery across agencies evaluating the most effective programs and thought about which job or agency suited their employment interests.

Combining both perspectives had a great effect on the human services students. They returned from this experience with motivation and renewed purpose. Not only were they thinking in terms of skill development and employment, they saw the importance of advocacy and better understood their responsibilities as citizens in a democratic society. Student leaders were able to help the service learning students understand concepts like client self-determination, confidentiality, and blaming the victim while developing and reinforcing their own skills as human services professionals, leaders, and educators.

Conclusion

Clearly, service learning and human services perspectives overlap in these two cases; the demarcation between human services education and service learning is not that clearly indicated in actual situations. It is important to note, though, that the two approaches do not simply reinforce the same learning but rather take the same situations and help students look at them from two different vantage points. The systems concept of equifinality is demonstrated as students begin their analysis from different perspectives and reach similar learning and understanding about themselves, others, and society.

Service learning courses in any discipline can raise student awareness of significant social issues and problems. This exposure to human needs and community responses can raise the level of civic awareness and commitment as students leave the academy and pursue their life goals. Service learning experiences can help students make important connections between their academic work and the larger world. For example, a biology major who is involved in a service learning project to monitor water quality in a poorer neighborhood can have a greater sense of how her discipline and the world outside of academics intersect.

Concerns about using service learning experiences in any discipline primarily fall into two areas. First, without proper guidance to assist in the reflective component of service learning, students may easily adopt a “blame the victim” mentality, where those who are less fortunate can be judged as lazy, unmotivated, willing to accept failure, or any number of other stereotypic perspectives. Without a mechanism to help them process what they have experienced, such as Kiser’s Integrative Processing Model (Kiser, 1998), it could be easy for students to ignore social forces that shape the lives of themselves and others.

A second concern, somewhat related to the first, is that service learning does focus on student learning rather than client needs. Service learning experiences are designed to help students broaden their frames of reference by interacting with situations they might otherwise not know existed. The focus of this experience, though, is to help students examine their own learning first and the needs of the clients second. Students can get so caught up in their own learning that they lose sight of those service recipients who are, in fact, teaching them. A strength that service learning experiences have in the helping professions, such as human services, is that the focus on client needs is more closely coupled with student learning, helping to keep both in balance.

One advantage of combining the two approaches is that their value domains, though less clearly defined in service learning, support each other in their experiential academic pursuit as well as in the development of responsible democratic citizens. Acceptance, diversity, client self-determination, confidentiality, respect and dignity are human services values that can inform the practice of service learning in ways similar to their importance in the helping professions. Service learning principles that guide the pedagogical focus on civic engagement, reciprocity, and reflection are useful in informing human services courses. This suggests that a careful use of service learning in human services courses is appropriate and can enhance and support the experiential learning that is inherent in coursework in the helping professions.

References

Ash, S. L. & Clayton, P. H. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2),137-152.

Astin, A.W. & Sax, L.J. (1998) How undergraduates are affected by service participation. Journal of College Student Development, 39,251-263.

Battistoni, R. (1997). Service learning and democratic citizenship. Theory into Practice, 36, 150-156.

Boyer, E. (1994, March 9) Creating the new American college. The Chronicle of Higher Education, A48.

Boyte, H. C. (2004). Everyday politics: Reconnecting citizens and public life. Philadelphia; University of Pennsylvania Press.

Brill, N. & Levine, J. (2005). Working with people: the helping process. New York: Pearson.

Chapdelaine, A., Ruiz, A., Warchal, J., & Wells, C. (2005) Service learning code of ethics. Bolton: Anker Publishing Company, Inc.

Colby, A., Ehrlich, T., Beaumont, E., & Stephens, J. (2003). Educating citizens: Preparing America’s undergraduates for lives of moral and civic responsibility. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Creighton, S. (2008). Significant findings in campus-community engagement: Community partner perspective. Journal for Civic Commitment, 10.http://www.mc.maricopa.edu/other/engagement/Journal. Retrieved July, 28, 2008.

Ersing, R.L., Jetson, J., Jones, R. & Keller, H., (2007). Community engagement’s role in creating institutional change within the academy: A case study of East Tampa and the University of South Florida. In From Passion to Objectivity: International and Cross- Disciplinary Perspectives on Service learning Research. Gelmon, S.B. & Billig, S. H. eds. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc.

Eyler, J.S., & Giles, D. E. Jr. (1999). Where’s the learning in service learning?San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Eyler, J. S., Giles, D. E., Jr., Stenson, C. M. & Gray, C. J. (2001). At a glance: What we know about the effects of service learning on college student, faculty, institutions, and communities, 1993-2000: 3rd Edition. Nashville, TN: Vanderbuilt University.

Fiddler, M. & Marienau, C., (2008). Developing habits of reflection for meaningful learning. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 118, 75-84.

Harkavy, I., (2004). Service learning and the development of democratic universities, democratic schools, and democratic good societies in the 21st century. In Welch, M. & Billig, S. H., (eds). New Perspectives in Service learning:; Research to advance the fields. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Kiser, P. (2008). The Human services internship: Getting the most from your experience, 2nd ed.. Belmont: Thompson Brooks/Cole.

Kiser, P. M. (1998). The Integrative processing model: A framework for learning in the field experience. Human Service Education, 18, 3-13.

Livney, D. (2008). Keeping mind in mind: Reflection and mentalization in the service learning classroom. Psychoanalysis, Culture & Society, 13 (2), 205-214.

Macy, J. (1994). A model for service learning: Values development for higher education. Campus Activities Programming, 27:62-69.

Miron, D. & Moely, B. (2006). Community agency voice and benefit in service learning. The Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 12 (2).

Rogers, C. (1958). The characteristics of a helping relationship. Personnel and Guidance Journal, 37, 6-16.

Sandy, M. & Holland, B. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. The Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13 (1).

Schwartzman, R. (2007). Service learning pathologies and prognoses. Paper presented at the National Communication Association, Chicago, IL.

Schultz, P.A. & Witt, S.D. (2004). Everybody wins: how service learning benefits students and the community. Education and Society. 22: 35-45.

Traini, E. P. (2008, May). Even in hard times, colleges should help their communities. Chronicle of Higher Education, 54(36) 36.

Woodside, M. & McClam, T. (2006) An introduction to human services. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

Westheimer, J. & Kahne, J., (2002, April). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

About the Authors:

Bud Warner, Ph.D., is an associate professor of Human Services at Elon University where he teaches in the areas of program design and assessment. He has previously worked as a social worker in child welfare and juvenile justice, and as both a teacher and an administrator in higher education. His research interests are in program evaluation.

Phone: 336-278-6407; Email: bwarner3@elon.edu

Beth Warner, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of Human Services at Elon University where she teaches in the areas of poverty, social welfare policy, and social change. She has previously worked as a social worker with homeless and low-income women and children. Her research interests are in service learning and empowerment of marginalized populations.

Phone: 336-278-6464; Email: bwarner2@elon.edu