In this article I will discuss the impact of a required campaign internship component in my American National Government classes during the Fall 2004, Summer 2006, and Fall 2006 semesters. After reviewing the logistics, subject matter, and results of adding a civic engagement component to this course, I conclude that the experiential learning component had a dramatic impact on the students’ understanding of and appreciation for the subject matter. The experience also dramatically increased the students’ interest in participating in government and their willingness to take an active role as citizens.

American National Government

At the University of South Florida St. Petersburg (USFSP), American National Government is an introductory level, required course, not only for Political Science majors, but also for a variety of other majors on campus. In the Fall 2004 semester I added a political campaign internship requirement to the course for the first time. (In the event that students were unable to intern on one of the campaigns, they were permitted to substitute a research paper in lieu of the internship requirement. Very few students took the research paper option.)

Students were unaware of this civic engagement requirement when they registered; it was quite an unpleasant surprise when they learned of this requirement as we reviewed the course syllabus on the first day of class. Indeed, I later learned when reviewing the Pre-Test Surveys, journal entries, and internship papers that many students considered dropping the class after they learned of the internship requirement. Consider these sample comments:

I have to admit that upon hearing that we would be completing an internship for a grade in our American National Government class, I was hesitant. Politicians? Three hours a week? Did I really want to devote my time to a cause I wasn’t sure I supported?When I first received the news that we would have to volunteer twenty-five hours on a political campaign, I was immediately filled with dread. Politics was something I just didn’t care for.

The internship component was worth twenty percent of students’ final course grade. The requirements included the following: work twenty-five hours on a political campaign, keep a journal detailing internship experiences and lessons learned, write a five-page paper about the internship experience, keep a log of hours worked at the placement (and have the supervisor sign-off on the hours), and return an evaluation of student performance filled out by the internship supervisor.

During the third week of the semester, I invited representatives from every campaign to come and speak to the class as a part of a “Campaign Internship Job Fair.” The candidates and/or their campaign staff spoke to the entire class, and then, after all of the presentations, campaign representatives met with interested students one-on-one. This individual time with the campaign staffers, prior to final selection of their internship placements, allowed the students to ask their potential supervisors questions and to get a sense of the kinds of projects that would be assigned. As I learned when reading the Pre-Internship Surveys, very few, if any, students had previous campaign experience. Most students found the prospect of working on a campaign to be daunting, and they had no idea how to go about getting involved in such an activity. Meeting with their potential supervisors helped ease the students’ anxiety.

Students selected their campaign placements, but I arranged all of the internships on behalf of the students. While this created extra paperwork for me, it helped the students to feel more comfortable with the process. It also allowed me to develop a working relationship with their supervisors, something that was useful when I needed to step in to resolve issues and when I evaluated students’ performance at the conclusion of the campaign. I created an internship application and other paperwork (including liability waiver and supervisor evaluation form) to facilitate this process.

The selection of a campaign was itself a learning process. Students were compelled to think about their party identification and about their political values. As one student pondered in her journal, “Was I a Democrat? Was I a Republican?” Another remarked, “If not for this internship assignment, I wouldn’t have given a second thought about who was running for what, or which party I sided with the most.”

Students interned on a variety of campaigns throughout Tampa Bay. Depending on the semester, students worked for candidates running for President, U.S. Senate, U.S. House, Governor, Florida Senate, Florida House, or campaigns to defeat/support constitutional amendments. My classes were closely divided between Republicans and Democrats.

The Tampa Bay region is not only the bellwether for Florida, but also it is the anchor of the I-4 Corridor, the battleground region of the state. During the 2004 presidential and the 2006 gubernatorial campaigns, both parties fought hard in Hillsborough (Tampa) and Pinellas (St. Petersburg) Counties. All students had the opportunity to meet their candidates at multiple events, and they had the choice of several local field offices in each county.

In addition to the campaign internships, I sponsored other election-related activities for the class, such as debate-watch parties. These debate-watch parties gave us another forum in which we could watch the candidates and discuss the campaigns. We opened up the debate-watch events to our campus community, and I was pleased with the large turnout. During our post-debate discussions, I was proud of my students, as they drew on their internship experiences and newfound expertise while discussing their reactions to the presidential candidates with our colleagues on campus.

Pre- and Post-Internship Survey Results

I administered surveys in class before and after the internships in an attempt to measure the students’ attitudes towards campaigns, politicians, elections, and American politics. The surveys also included a few questions from the Public-Release Questions from the 1988 NAEP Civics Assessment. (Niemi and Junn, 1998) I wanted to learn whether the internship experience changed their views of politics and whether the internship enhanced the students’ understanding of political campaigns.

Overall, the Pre-Internship Survey results painted a grim picture of what the students thought about American government and politics. Students displayed little confidence in the political system and very little confidence that participation in campaigns – or even voting – would make any difference at all. After reading through the students’ surveys and compiling the results, I doubted that twenty-five hours of work on a campaign would move students to reconsider their firmly held cynical beliefs. Still, I hoped that the students would learn about campaigns and the issues dominating the election cycle. Much to my surprise, not only did students learn a great deal about campaigns, but also they were inspired by the experience.

When asked about the their attitudes towards campaigns in the U.S., students focused on the importance of fundraising, the influence of special interests, and their disgust with negative television advertisements. Students tended to look at elections as providing a “lesser of two evils” choice. The 2000 presidential election here in Florida increased students’ apathy and cynicism; several students mentioned the 2000 election as proof that their votes would not be counted and as evidence that our elections are “not valid.” One made a disturbing comment about his/her feelings about campaigns gleaned from other political science courses he/she had taken: “The classes I have taken before make it very difficult to believe that individuals can make a difference.”

When asked about their attitudes towards politicians and elected officials, students responded that they are “somewhat able to be trusted,” “shady,” “favor wealthy corporations,” “corrupted by lobbies and corporate interests,” “very removed from the general population, not very plausible to get your voice heard,” “even though a candidate has a position on a topic, that doesn’t mean that he/she will be able to change it,” and “overpaid and underworked.” Another student lamented that “There are too few great thinkers in government today. The brilliant minds stay away because of muckraking and corruption.” Overall, the answers in the survey provided a dismal picture of student perceptions of their public servants.

Regarding their expectations for the internship, most students said that they hoped to learn first-hand about how campaigns are run. However, they confessed that they were nervous about the prospect of working on a political campaign, and they were unsure of what to expect when reporting for duty.

After reading through the Pre-Internship Surveys, I did not expect to see much of a change in student attitudes toward politics, politicians, or political campaigns. However, there was a significant difference in the Post-Test responses.

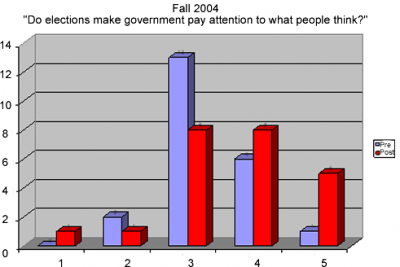

In answer to the question (on a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being “not much” and 5 being “a great deal”), “Do you feel elections make the government pay attention to what people think?” twice as many students responded “4” or “5” on the Post-Internship Survey. In terms of percentage of the respondents, during the Fall 2004 semester, 32% of the students responded “4” or “5” in the Pre-Test Survey; 57% responded “4” or “5” in the Post-Test Survey. (See bar graph, below) During the Fall 2006 semester, 39% responded “4” or “5” in the Pre-Test Survey; 65% responded “4” or “5” in the Post-Test Survey.

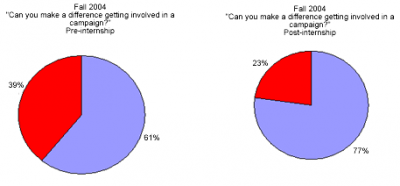

During the Fall 2004 semester, twice as many students responded “yes” to the question “Do you think you can make a difference in changing the direction of this country by becoming involved in the 2004 presidential campaign?” (See pie charts, below.)

In the short answer section, students explained that they learned that they could make a difference in their communities by becoming involved in politics. Students felt that they learned what “a campaign was all about, what it means to be involved and the importance of people to a candidate’s success.”

Students also expressed a change in attitude regarding whether the internship assignment was a worthwhile endeavor. Despite their initial skepticism about this assignment, all students recommended including this kind of assignment in futureAmerican Government classes. Their (anonymous) answers ranged from “yes” to “absolutely.” One student even thought that the internship component was “essential to this course.” They talked about the benefits of their first-hand experience and their greater appreciation for the subject matter. Students said that it was an enjoyable and an educational experience. In response to the question of whether the internship met their expectations, the overwhelming response was that it surpassed expectations:

It surpassed my expectations. I learned so much and met so many people.I thought it would be boring – but – the internship was one of the best things I have done since I have been in college.

I expected to learn what goes on behind-the-scenes and to get a feel for what my candidate stood for. Yes [it met my expectations], I had an enjoyable time and got a great deal out of the experience and learned how a campaign works.

Students also talked specifically about what they learned from their internship: campaign tactics, voter contact activities, and different methods of voting (absentee, early vote, and Election Day). One student remarked “The campaign internship met all of my expectations. I learned the importance of teamwork, about campaign finance, PACs, FEC reports, canvassing, voter turnout, etc.”

Excerpts from Students’ Internship Journals and Papers

The Pre- and Post-Internship surveys were anonymous. Students also were required to keep a journal of their internship experiences as well as to write a paper about what they learned about campaigns and elections as a result of their campaign work.

Early in their journals, students expressed trepidation about the internship. One student remarked that “This is the first campaign that I had ever been involved with, as well as my first time voting, so to me the entire experience was like walking into some odd dream. . .”

After the initial entries, I read about the various candidate events that the students attended. Students planned and attended rallies and fundraising events. They went to lunch with campaign staff and used those opportunities to learn more about life on the campaign trail. Students indicated that they had increased access to the candidates due to their internship experience (e.g., “rope line” tickets to events when they were attendees).

Students engaged in a variety of voter contact activities: absentee ballot and early vote recruitment, phonebanking, data entry, visibility, training and recruiting volunteers, canvassing, and Get Out the Vote activities on Election Day. Students described their training for and participation in these various activities, and they explained what they learned about grassroots organizing in the process. Most students seemed to take the ups and downs of voter contact in stride. One student described his first day canvassing as follows:

My first day as a canvasser included very little training. It turns out that canvassing is not rocket science, but is best learned by practice. The only challenge is to keep the array of facts and statistics in memory and fashion them into a conversation that is relevant to the interests cited by the person you are speaking to when you ask them what issues concern them the most. . . . I gradually became more comfortable talking to complete strangers about politics and asking them to tell me who they’re going to vote for. This being the nature of the job, it seems rude and angry responses are unpleasant but not unexpected.

The classes were almost evenly split between Republicans and Democrats, so many of the students worked on losing campaigns. I was interested to learn how the students, who by Election Day had become invested in their respective campaigns, dealt with the loss. While those who were on the losing side were not pleased with the outcome, they were not discouraged from future participation.

I was disappointed that the candidate I supported lost the county, state, and country I worked in. But this disappointment drives me to do more during the next election cycle, on both the local and federal level. I’ve learned a great deal about how it is to work on a federal campaign and also how difficult and time-consuming it is. But even in defeat, it is still worth it to work for a cause that one believes in.This is when I realized that even though they had lost, they [the campaign staff] would still fight for what they believed in. This is one of the greatest freedoms that we have: the ability to speak out against what we believe is wrong, and then to be able to fight for change.

Students reported that the internships increased their interest in politics. One student explained in his internship paper: “My interest in politics has grown tremendously over the past few months, and I think I can attribute this to the time I spent interning at the Bush/Cheney headquarters.” Another student explained that “Before doing [the internship] I really didn’t care about politics and how it worked, but now I actually understand what is going on . . . I would say this was a great learning experience for me.”

Students were generally more positive about politics, politicians and campaigns in their post-internship reflection pieces. One student explained, “I came to the assignment with a very pessimistic outlook on politicians and government as a whole. I came out with a new understanding of the political arena and the realization that the benefits of government far outweigh the negative undertones that so many associate with the politics of America.”

Students also believed they were more knowledgeable about politics, and reading through the papers, it was evident that they did learn a great deal about campaigns and elections as a result of their internships. One student described herself as a more educated voter this election cycle: “Without my internship experience, I would have voted based on likes and dislikes versus real political issues, but because I got involved I was educated in all aspects.”

This increased understanding led to an increased comfort level talking about politics and the issues dominating the election cycle. One student explained in her internship paper: “Overall, I feel that working on this campaign made me feel more like a citizen.’ I found myself paying more attention to politics on the news, and I even watched the debates. I also feel I became more outspoken about my candidate of choice. . . I really just enjoyed the feeling that I was in some way making a difference by interning on this campaign.”

Students were much more talkative in class discussions than they were prior to becoming involved in politics themselves. According to their responses in the Pre-Internship Surveys, most students in the class were taking American National Government because it was a required course, and they had little or no interest in American government. That changed over the course of the semester, as students’ participation in the internship heightened their interest in and willingness to talk about politics.

Despite the overwhelmingly negative response to the Pre-Internship Survey question “Do you think you can make a difference in changing the direction of this country by becoming involved in the campaign?” many students reported that they believed they did make a difference by becoming involved in the election:

I think we all learned something from this election about the strength each and every one of our voices holds. . . . I learned a great deal about how the whole election process works. For a first-time voter like me, being involved helped me understand just how important it was for me and people my age to get out and vote. I am proud of the support and effort that I put into this election year.I learned that one person really can make a difference. When I think of all the people I visited and how encouraged they were and how some of them changed their vote, and to know I had a part in making that happen makes me feel good to be a Republican and great to be an American. For me this was a life-changing event because I feel that not only have I had an impact on history but I was able to exercise the rights that were paid for by millions of men and women who have served in our armed forces over the past 250 years. Working on this campaign taught me how elections run and how each person is needed for the common goal of the group. I learned where all the money goes, who does what, and I learned that the American public is not as apathetic as politicians would like to think they are, and, finally, I learned that I could make a difference.

To my surprise, students once reluctant to get involved in politics declared that they were inspired to take part in future campaigns.

This was the first opportunity I had to work for a political campaign. I learned many things during my time as an intern. Most importantly, I learned how much work, both paid and unpaid, goes into a political campaign. It was a wonderful opportunity, and I cannot imagine another campaign going by that I don’t volunteer for.This experience as a whole was very interesting, very educational, and very enjoyable. I enjoyed it so much that I would not hesitate to help with the campaign of the Republican who attempts to replace President Bush.

After reading about how reluctant students were to participate in the internship component of the course, I was also surprised to read that, in the end, the students were grateful for the experience working on a campaign:

Working on this campaign has affected my life in ways I never imagined. I am now more driven than ever to get involved and make a difference. I have come out of this experience with a tremendous amount of respect for those who work on campaigns and for those who run for office. The dedication and commitment is commendable. They came in as individuals and left as a family. I was privileged enough to be a small part of that family. It was with a heavy heart that I said goodbye to the campaign and all the staff. I have come away from this with new friends, contacts, and a knowledge I had never expected.

I wondered whether the dramatic turn-around in student attitudes that I witnessed during the 2004 presidential campaign would be replicated when I added the internship component during the 2006 mid-term elections. I found that students were just as enthusiastic about the internship experience in the mid-term election in 2006 as they were in the 2004 presidential election:

I assumed I would be unmotivated, that the work would be a hassle more so than it would be an enjoyable learning experience . . . . [I now look back on the internship as an] opportunity that taught me more about our government, about the campaign process and about the candidate’s themselves.

This increased interest and participation in the 2006 election that I witnessed among my students is especially impressive against the back-drop of the lowest voter turnout in Florida in 50 years (47%) and a youth voter turnout in Florida of only 18% (the 47th lowest youth voter turnout rate in the nation). (Lopze, Barrios Marcelo, and Kirby, 2007)

Students also talked about the variety of skills that they developed during their internship. Many believed they developed their communication, teamwork, leadership skills during the course of the semester. Students discussed the benefits of the experiential learning component of the course not only in terms of the skills they developed and the connections that they made, but also in terms of the knowledge that they gained about the course material. Consider these sample student comments:

While it is certainly possible to learn all the facts of the election process in a classroom context, I now believe that the only way to truly understand the process is to become involved in a campaign itself. . . . That is more meaningful and memorable than any textbook or article could be.This internship helped me come to the realization that politics is definitely not something to blow off as unimportant. Luckily I found this out at 19-years-old, during the first election I could legally vote in. . . . I would suggest that everyone under the age of 25 should participate in something like this. . . My guess would be that most of them would come out of the experience with a vastly different, more enlightened perspective on politics.

One of the questions included in the Pre-Test survey was “What does it mean to be a ‘citizen’?” The answers presented a view of citizenship that was rights-based with the citizen’s only obligation to vote in elections. Students developed a deeper notion of citizenship during the course of the semester. One student concluded in his internship paper that “Democracy is a job.” Even those who retained that rights-based notion of “citizen” defined in terms of suffrage, students were more enthusiastic about the importance of exercising the franchise:

I gained a new, more optimistic outlook on the world of politics. No longer will I overlook my right to vote. I will take full advantage of the gift the Constitution protects.

Reflections on the Addition of a Required Campaign Internship in American Government

Integrating a campaign internship component into a course about American government can have extraordinary results. To be sure, adding this civic engagement requires a great deal of extra effort on the part of the instructor and on the part of the students. For my part, I arranged the internships, monitored the students’ progress, intervened when issues arose, and worked with supervisors from eight or more campaigns. Students at USFSP, many of whom are “non-traditional,” had to balance work, family, and school responsibilities with the twenty-five hour campaign internship requirement. In the end, all of the extra effort was rewarded.

Students were enriched by the experience in ways they never expected. For me, as a professor, to see the students engaged in the material, energized and inspired to get involved in politics (something that in their Pre-Internship Surveys they described as completely unappealing) was truly rewarding. Students registered for and attended the class only because it was a requirement to graduate – not because they had any interest in American government, and certainly not because they wanted to work on a campaign.

The Pre-Internship surveys painted a bleak picture of what students thought about American government, politicians, politics, campaigns, and elections. While youth cynicism and apathy is well-documents in the literature, my students’ negative attitudes seemed to be exacerbated by their experience with the 2000 presidential election here in Florida. Not only did students think that participating as a volunteer would be a waste of time, but also students did not think it was worthwhile to vote (and lacked confidence that their votes would be counted). Students seemed to focus exclusively on the influence of money and special interests in politics.

When reading the Post-Internship Surveys, Journals, and Internship Papers, I was overwhelmed by the transformation – in both presidential and mid-term elections. Students found that they could make a difference by getting involved in the election – as campaign volunteers and as voters. They reported that they felt as if “for the first time in their lives” that they were “citizens.” Even those students on the losing side (about half the class) were not discouraged from future participation.

It is true that in Tampa Bay (the battleground region of a battleground state) we were spoiled by a great number of presidential, gubernatorial, and senatorial candidate visits and significant campaign resources spent in our region (on television and in the local field operations). All of the students were able to see and meet their candidates and other high-ranking elected officials in their respective parties. Still, all of this would have passed the students by if it were not for the campaign internship requirement. It was the internship component of this course that got the students engaged with the material that we were discussing in class. The internship brought the issues, and their importance, to life for my students.

There was a profound difference during lecture as the semester wore on (especially as it got closer to the election). Students were much more engaged with the material, and they were more active participants in class discussions. They followed current events, paid more attention to the news, and brought up relevant issues during lectures. Our discussions were much more robust, and students once too shy to participate later found the confidence to speak up. After being trained to go door-to-door and to call complete strangers, suddenly the classroom was not as intimidating.

I conclude with a student quotation that encapsulates why I believe that incorporating a campaign internship in American Government can have a profound effect on the students’ civic education:

This experience was very influential to me. I feel like this internship and the course has opened a new chapter in my life. I am not saying this will be a new career path. I am saying that every election going forward, I will take more seriously and try to get involved in any way that I can. I think my understanding of American Government has definitely increased. It was a great learning experience. I wish more of my classes were like this one. It was great having the opportunity to be involved in an experience like this.

Incorporating an internship within core Political Science courses can have a dramatic influence on students’ educational experience. As this example demonstrates, students became engaged and interested in the material as a result of their internship experience. Students left the course having learned more about American government, and they cultivated a desire to become active citizens — and realized the value of theirparticipation in American constitutional democracy.

References

Lopez, Mark Hugo and Karlo Barrios Marcelo and Emily Hoban Kirby. 2007. CIRCLE Fact Sheet, “Youth Voter Turnout Increases in 2006.”

Niemi, Richard G. and Jane Junn. 1998. Civic Education: What Makes Students Learn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

About the Author:

Dr. Scourfield McLauchlan is an Assistant Professor of Political Science, Founding Director of the Center for Civic Engagement and campus Pre-Law Advisor at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg, where she teaches courses in American Government and Public Law. Her latest book, Congressional Participation as Amicus Curiae before the U.S. Supreme Court, explores how Members of Congress attempt to influence Supreme Court decision-making in specific cases. In addition to her scholarly activities, Professor McLauchlan has extensive experience in American government and politics. McLauchlan worked at the U.S. Supreme Court, the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee, the U.S. Department of Justice, and the White House. A veteran of several presidential campaigns, she has managed statewide operations across the United States, from Portland, Maine to Portland, Oregon. Phone:727-873-4956; Email:jsm2@stpt.usf.edu