Encouraging Civic Engagement on Community College Campuses

Recent years have witnessed a decline in civic engagement among college students. According to an article in Proprincipal (‘Civics Classes,’ 2003), young people display a consistent lack of knowledge of American government, while others feel apathy towards the process of democracy. In a national survey among 15 – 26 year olds, 48% could identify their governor’s political party, 40% could name which party controls congress, 22% could name the party that controls their state’s legislature, and 10% could identify U.S. House Speaker Dennis Hastert (Tarrant, 2004).

According to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, this lack of knowledge may be due to teachers’ concerns over negative repercussions when they address politically controversial issues, as well as to cuts in funding for extracurricular civic-related activities (‘Report’, 2003). According to Bok (1982) and Checkoway (2001), ‘Student disinterest in the social good is not surprising to some, given academia’s distance from real-life needs and concerns’ (as cited in Rhoads, 2003). From the perspective of a multicultural and increasingly global society, liberal education has a responsibility to help students develop a multifaceted character, proficient at dealing with various cultures (Rhoads, 2003).

Within the last few years, the importance of civic engagement has been heavily emphasized. Regina Hughes, the Director of the Center for Scholarly & Civic Engagement and Coordinator of Service-Learning for the Collin County Community College District (CCCCD), defines civic engagement as ‘active, intentional participation in the community with the purpose of affecting positive change while developing a sense of civic responsibility and an appreciation of what it means to live in a democracy’ (personal communication, Nov. 18, 2003). Hughes is committed to civic engagement and believes students have a vested interest in being civically engaged as well. Apparently, Hughes is not the only one who believes this; in the wake of 9/11, President George W. Bush called on all Americans to commit themselves to 4,000 hours of community service. In response to the demand for people, especially youth, to become more civically involved, more colleges are encouraging student participation in civic engagement activities by becoming members of the National Campus Compact. National Campus Compact is an alliance of presidents from over 900 public and private colleges and universities, dedicated to increasing civic involvement and engagement on college campuses.

In 2003, Collin County Community College, as one of 20 community colleges in the nation, received recognition from the National Campus Compact for being a model of exemplary practices related to civic engagement (‘CCCCD recognized’, February 13, 2003). Collin County Community College, along with 18 other colleges and universities in Texas, participated in a national Civic Engagement Week from February 17 to 21, 2003. A main objective for civic participation at CCCCD was the opportunity for students to express ideas and opinions regarding current controversial topics of civic concern on physical ‘discussion boards.’ These discussion boards were provided at each of the three participating campuses at CCCCD. Subsequent reflection on Civic Engagement Week revealed that the utilization of discussion boards provided an avenue for democratic dialogue, and thus provided an opportunity for students to be civically engaged.

An increase in the involvement of students in civic engagement is essential, not just in enhancing their college experience, but also in affecting the course of democracy. ‘Democratic conversation between citizens and government has always been central to the ideal, if not practice, of democracy’ (McCoy & Scully, 2002, p. 127). In order for democracy to function at a healthy capacity, it is necessary for the community to be actively engaged and involved in the democratic process. In the Campus Compact President’s Fourth of July Declaration on the Civic Responsibility of Higher Education, he stated,’ . . . now and through the next century, our institutions [of higher education] must be vital agents and architects of a flourishing democracy’ (Civic Engagement, 2004).

The years in university are crucial to the development of our society and its commitment to democratic citizen involvement. Universities and colleges are breeding grounds for leadership, and if commitment to involvement is not taught at this level, civic engagement in our communities will decline as the graduated students enter the workplace and daily life. In 1916, John Dewey declared, ‘A democracy depends upon the willingness of learned citizens to engage in the public realm for the betterment of the larger social good’ (as cited in Rhoads, 2003, p. 25). As educated individuals, college students are held responsible by this statement to be civically engaged.

During the formative college years, students have the chance to participate in activities where ‘traditional campus divisions, such as those between students’ affairs and academic affairs, and between disciplines and departments are suspended in the interest of a broader view of educating students as whole individuals whose experience of community engagement is not artificially confined by disciplinary distinctions’ (Hollander, Saltmarsh, & Zlotkowski, 2001, p. 4). These experiences of becoming unified around a goal and crossing over naturally prohibitive boundaries provide real life training in sacrificing differences for a common purpose. This skill of unification beyond natural barriers is essential in our current world, as can be seen so clearly when observing daily news media coverage of any peace talks and/or alliance treaties that surround wartime hostilities or civil turmoil abroad.

Another benefit of civic engagement is that of one can develop a selfless perspective. Astin (1998) stated, ‘A more recent concern is that students are more committed to career interests than the kind of idealism that liberal learning traditionally sought to foster’ (as cited in Rhoads, 2003, p.25). A single, self-focused, ego-centered perspective has begun to dominate our college culture, and it is of concern to some because of the absence of community awareness. Regina Hughes stated that civic engagement is important because it:

Enhances people’s understanding of something other than themselves and their environment and it can be a vehicle for positive social change. The community has the opportunity to be a co-educator and to benefit from student contributions of creativity, problem solving and desire to make a difference. Students are exposed to various opportunities to expand their knowledge about the community, are encouraged to take a leadership role in making positive changes, and therefore are instilled a sense of civic awareness and civic responsibility, while learning democracy is not and was never intended to be a spectator sport (personal communication, November 18, 2003).

There are authentic needs in every community, and those exact needs vary by area, size, demographics, and so on, it is important to recognize that in order for specific community needs to be met, the needs must be addressed, and in order for any of these needs to be addressed, it is essential that the citizens of the community become involved. ‘Citizen-driven democracy is the best avenue for strengthening and reforming civic life’ (McCoy & Scully, 2002, p. 119). Democracy is intended to make all voices valuable. College students are a strong element of our society, and thus should not be a neglected portion of the population. In order for students’ needs and opinions to be heard, students must have a voice. Americans between the ages of 18 and 24, account for about one in every seven voters (Tarrant, 2004). While voting participation shows a decline in all age groups, it is more pronounced with younger people (Tarrant, 2004). The reason young people give for not exercising their right to vote is; they feel politicians don’t pay attention to them. Politicians claim they don’t pay attention to young people because they don’t vote. This lack of understanding may result in a ‘mutual cycle of neglect’ (Tarrant, 2004).

According to Hughes, through service learning ‘students can make some really profound changes, but they have to find their voice and know how to articulate it’ (personal communication, November 18, 2003). An example of this power and influence can be seen in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1960, when a group of black college students lined up at the counter at a local diner, sat down, and refused to move (Hughes, personal communication, November 18, 2003). This single event set off a huge movement for civil rights in America. ‘When students’ internal passion for justice and change is stirred up and channeled toward community involvement and civic engagement, the potential for good is overwhelming’ (Hughes, personal communication, November 18, 2003). ‘Higher education,’ claimed Boyer (1996), ‘must become a more vigorous partner in the search for answers to our most pressing social, civic, economic, and moral problems, and must reaffirm its historic commitment to what I call the scholarship of engagement’ (as cited in Hollander, et al., 2001, p. 4).

Using Student ‘Discussion Boards’ as a Tool For Measuring Civic Engagement on College Campuses

Recognizing the necessity of promoting civic engagement among college students, many colleges and universities have participated in national Civic Engagement Weeks. An important part of Civic Engagement Week, 2003 at Collin County Community College was the use of physical discussion boards, and the theme, ‘Let Your Pen Do the Talking.’ The boards were constructed out of bright yellow butcher paper and placed in high traffic areas at each of the 3 participating campuses at CCCCD. A current controversial issue of civic concern was written at the top of the discussion board, leaving the majority of the space for students to write down their opinions (Hughes, personal communication, November 18, 2003).

According to recent studies, discussion boards prove to be an effective tool in the academic environment. Professors have been utilizing the Internet to form discussion boards in an effort to augment the classroom experience. The term discussion board refers to an ‘on-going site where participants are free to log in at any time, read other’s postings, and post their own thoughts’ (Maloney, Dietrich, Strickland, & Myersburg, 2003, p.275). Professors establish discussion boards with the intention for them to serve as a forum where students exchange ideas, receive peer reaction on specific topics, and question their own beliefs (Overbaugh, 2002).

Similar to what was done with the discussion boards at CCCCD, instructors typically post a question or prompt to stimulate discussion between students (Wickstrom, 2003; DenBeste, 2003; Maloney, et al., 2003). Students are encouraged to initiate their own threads. ‘Discussion threads’ are a series of comments that build on previous responses with original thoughts or questions. Professors observed that students’ questions, or posted ideas generated more conversation than did their own questions and ideas (Wickstrom, 2003). By encouraging postings that build on previous postings, instructors are leading students toward effective, ‘asynchronous dialogue’ (Overbaugh, 2002). In one study, the instructor posted three subjects for discussion, each meant to be a bit controversial in an effort to trigger student feedback and spin-off discussions (Overbaugh, 2002). Questions and topics that students viewed as controversial provoked the highest number, as well as the highest quality of participation. Controversial topics and questions tend to cause students to consider their own beliefs. The key is identifying topics that are appealing and thought-provoking to students (Overbaugh, 2002). A number of students at CCCCD indicated a desire for additional topics of interest to be added, and were overheard by professors carrying their conversations from the discussion boards to the classrooms.

Instructors who participated in the aforementioned studies indicated a number of potential benefits to using discussion boards. Instructors felt the use of discussion boards could nurture a sense of community, from which students seem to benefit (DenBeste, 2003; Quick & Lieb, 2001; Overbaugh, 2002). Since discussion boards ‘allow each user an equal voice, or at least an equal right to speak’ (Selwyn 2000, 751), a number of professors thought the use of discussion boards would provide students who were too shy to speak in class an effective outlet (DenBeste, 2003; Wickstrom, 2003; Selwyn, 2000). The building of social bonds through the kind of group connection provided by discussion boards has important socio-affective and cognitive benefits (Woods & Ebersole, 2003). Discussion boards have the ability to promote the advancement of reading and writing skills, as well as to improve critical thinking (DenBeste, 2003; Wickstrom, 2003; Overbaugh, 2002). Discussion lists also generate deep critical thinking (Jaeger, 1995; Mikulecky, 1998, as cited in Overbaugh 2002). According to Barab, Thomas, & Merrill (2001), ‘asynchronous text-based communication’ allow students to carefully formulate their opinions and thoughts (as cited in Overbaugh, 2002).

Wickstrom (2003), suggested that discussion is significant to the enhancement of skills required for the examination of a situation, which better enables a person to change them, if he/she so desires. If people articulate what they know, then they have the opportunity to reflect on it and make changes. An underlying purpose of asynchronous discourse is to assist students in their efforts to publicly express their opinions and afford them opportunities to build and cultivate their knowledge, the source of which is primarily their own experiences and those of their peers (Overbaugh, 2002).

The most compelling vision of an ideal democracy is one in which there are ongoing, structured opportunities for everyone to meet as citizens in these face to face settings, not only does everyone have a voice, but each person also has a way to use that voice in inclusive, diverse, problem-solving conversations that connect directly to action and change (McCoy & Scully, 2002, p. 119).

Overbaugh (2002), found the high level of cognitive effort displayed, indicated the possibility for discussion boards to function as a mode for ‘meaningful discourse that will help students move toward professionalism through offering, examining, and perhaps modifying preconceived notions.’

The studies conducted by Overbaugh and Wickstrom discussed several problems specific to computers and written communication in general. The inconsistency in students’ computer skills and access proved a challenge (Wickstrom, 2003; Maloney, et al., 2003). By allowing students to physically write on the discussion boards, CCCCD avoided this problem. Some students in previous studies hesitated to post anything because they were uncomfortable with other people reading what they had written, the environment was just too public (Wickstrom, 2003; Maloney, et al., 2003). CCCCD placed pens on strings, enabling students to write their comments quasi-anonymously. Written communication also presents problems, although. For example, there is an increased possibility for misinterpretation. Any type of written communication lacks nonverbal expressions such as facial changes and gestures, along with tone of voice and other refinements of communication (Maloney, et al., 2003). CCCCD had trouble interpreting some people’s comments. The comments could be viewed in a number of different ways. Since no one actually spoke to the writer and therefore could not hear their tone or observe other nonverbal cues, it was difficult to determine the writers’ intentions.

In addition, deciphering the order of discussion threads can be difficult. Messages can easily get ‘out of synch’ as one person introduces a new topic while two others carry on a conversation about an earlier topic (Maloney, et al., 2003). At CCCCD, trying to determine which comments went together also proved difficult. The only way to know if a comment was a reply to another statement was the writer typically drew an arrow to the original comment. If not for this, it would have been impossible to determine which comments were replies to others.

In analyzing the discussion boards from the 2003 Civic Engagement Week at CCCCD, the total number of responses and how they compared across campuses and discussion board topics was examined first. The total number of responses was calculated by campus and by topic, and then each response was subsequently categorized as ‘for,’ ‘against,’ ‘neutral’ or ‘non-applicable’ within each topic. For was defined as being ‘for’ the topic at hand, ‘against’ as against the topic, ‘neutral’ as neither for nor against the topic, and ‘non-applicable’ as completely unrelated to the topic.

In our research we analyzed ten topics, which consisted of; abortion, affirmative action, higher education budget cuts, free speech, gay rights, gender issues, immigration, racism, war and peace, and welfare. For examples of student comments, please refer to Table 1, which details some student responses to affirmative action. It may be noted that the perceived cognitive effort put into the responses varies per comment, and this pattern of varied effort was consistent across all subject headings. We did not attempt to formally assess the cognitive levels of each response and/or discussion, but simply noted that there was much diversity and that all levels of thought were represented. Table 2 shows the number of responses as percentages of total student enrollment. It appears that the Spring Creek campus had a higher percentage of student involvement (7.04%). The Spring Creek campus at Collin County Community College also maintains the highest enrollment, and most student-related activities are centralized to this campus. Yet, it should be noted that in the evaluation of data, there was no method for determining multiple responses by single students, and therefore the data cannot be accurately used to evaluate overall percentage of student involvement.

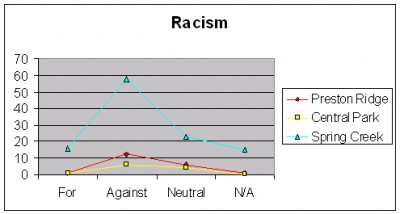

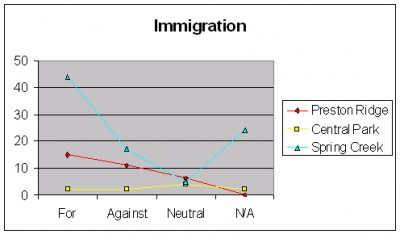

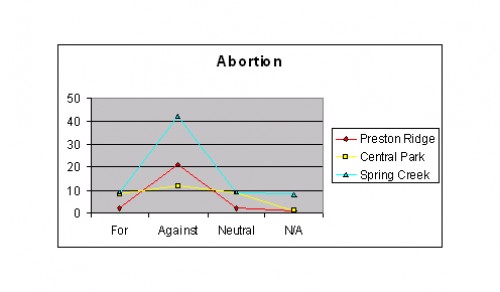

Table 3 details the number of responses both by campus and by topic. Racism was the most responded to issue at the Spring Creek campus (112 responses), immigration at the Preston Ridge campus (32 responses), and abortion at the Central Park campus (30 responses). Please refer to Figure 1 for an example of ‘for,’ ‘against,’ ‘neutral’ or ‘non-applicable’ analyses of this data.

Also evaluated, were the discussion threads from each discussion board. These were analyzed in order to determine which topics generated the most discussion among students. The results of these analyses revealed that the most discussion was generated by the topic of gender issues at the Spring Creek campus (36 threads), immigration at the Preston Ridge campus (15 threads), and abortion at the Central Park campus (12 threads) (See Table 4).

The responses were next evaluated for content per topic by finding themes to the student remarks. Once themes were determined, recommendations were formulated and submitted to administration. These were recommendations for further education of students in particular areas, as well as possible future programs intended to address the civic concerns of students at each individual campus (see Table 5).

After evaluating the 2003 activities, it has been determined that discussion boards perform a valuable role in the encouragement and promotion of civic engagement. This can largely be attributed to their anonymous nature, the individual self-interpretation by participants of the topic being discussed, and the stirring up of relevant conversation among peers.

This year, the National Campus Compact decided to devote an entire month to civic engagement activities. The mission statement for the National Campus Compact in 2004 is, ‘to provide an opportunity for the students and the community to address issues and promote civic engagement for the common good’ (‘Raise your voice,’ n.d.). Collin County Community College’s theme for this year’s discussion forum is ‘One Voice to Change the World.’ A particularly important topic that will be stressed this year is the 2004 presidential election. Last year, a Civic Engagement Team consisting of three members coordinated the activities for that week, which included the creation of a forum for students to express their views on a number of different issues facing society. This year’s Civic Engagement Team is composed not only of administration, but also of students. One of the changes planned for this year’s civic engagement discussion boards is to divide the boards by gender, thereby creating a variable for possible future studies. Another change is the use of universal topics at all three campuses for standardization purposes. Also, future analyses of statements could use level of cognitive effort, as was done in a previous study by Overbaugh (2002). In this particular study, the statements were categorized as low, medium, and high, based on the degree of thought required to formulate the statement. William Perry’s (1970) Model of Intellectual and Ethical Development was used to define the different levels of cognitive effort.

In conclusion, discussion boards have shown to encourage civic thought and discussion. They are effective venues for the anonymous sharing of opinions and concerns and they promote physical civic-related conversation. In addition to inciting civic thought among students, these boards are useful in educating faculty and staff of current controversial areas of civic concern. Although conversation is not equivalent to action, dialogue seems to stimulate thought and interest, and may encourage students to take the next step in engaging in their communities and in continuing to educate themselves in the important social issues surrounding them. Perhaps, discussion boards, along with other efforts by Collin County Community College to promote civic involvement, will fuel the interest and the desire of students to participate in civic activities, thereby assisting in the development of more socially interested, involved, and knowledgeable citizens.

References

CCCCD is founding signer of Texas Campus Compact. (2001, October 23). Retrieved February 8, 2004, from Collin County Community College website: http://www.ccccd.edu/academicnews.html

CCCCD recognized for service-learning and civic engagement programs. (2003, February 21). Retrieved February 8, 2004, from Collin County Community College website: http://www.ccccd.edu/academicnews.html

Civic Engagement. (n.d.). Service-learning. Retrieved February 10, 2004 from http://www.ccccd.edu/servicelearning/links.html

DenBeneste, M. (2003). Power point technology and the web: More than just an overhead projector for the new century. The History Teacher, 36, 491-500. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Hollander, E., Saltmarsh, J., & Zlotkowski, E. (2001). Indicators of engagement. In L. Simon, M. Kenny, K. Brabeck, & R. Lerner (Eds.), Learning to Serve: Promoting Civil Society Through Service-Learning. Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Maloney, M., Dietrich, A., Strickland, O., & Myersburg, S. (2003). Using internet discussion boards as virtual focus groups. Advances in Nursing Science, 26(4), 274-282. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

McCoy, M.L.& Scully, L. (2002). Deliberate dialogue to expand civic engagement: what kind of talk does democracy need? National Civic Review, 91(2), 117-136. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Overbaugh, R. (2002). Undergraduate education majors’ discourse on an electronic mailing list. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 35(1), 117-138. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Proprincipal. 2003, November. Civic classes increase civic engagement. 16(2), 10. Retrieved December 1, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Quick, R. & Lieb, T. (2000). The Heartfield project. T H E Journal, 28(5), 41-47. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Raise Your Voice campaign. (n.d.). Get informed: The origins of the ‘Raise Your Voice’ campaign. Retrieved February 23, 2003, from http://www.actionforchange.org/getinformed/origins-ryv.html

Report: ‘Fear factor’ holding back civics. (2003, June). District Administration, 39(6), 59. Retrieved October 20, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Rhoads, R. (spring 2003). How civic engagements is reframing liberal education. PeerReview, 5(3), 25-28. Retrieved October 10, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Selwyn, N. (2000). Creating a ‘connected’ community? Teachers use of an electronic discussion group. Teachers College Record, 102, 750-779. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

Tarrant, D. (2004, January 9). Going after the D’oh! Vote. The Dallas Morning News, pp. 1A, 6A.

Woods, R. & Ebersole, S. (2003). Using non-subject-matter-specific discussion boards to build connectedness in online learning. The American Journal of Distance Education, 17(2), 99-110.

Wickstrom, C. (2003). A ‘funny’ thing happened on the way to the forum. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 46, 414-424. Retrieved December 17, 2003, from Academic Search Premier database.

About the Authors:

The authors are Jennifer L. O’Loughlin-Brooks , professor of Psychology at Collin County Community College and her students from Psi Beta National Honor Society, the honor society in psychology for two-year colleges. Students spent an entire semester collecting and analyzing this data in order to help quantify civic participation at our institution. You can reach the author at 2800 E. Spring Creek Parkway, Plano, TX 75074, Collin County Community College, jbrooks@ccccd.edu, 972-578-5512

Table 1 – Student Responses Verbatum-Affirmative Action

- Hurts all Americans.

- Should have never started, or been allowed.

- “Only promotes un-education and un-competent workers.”

- Reply: “Does it promote improper grammar as well?”

- Transfers racism instead of preventing it.

- “Everyone should be given equal opportunity not at the sacrifice of others. There could never be an answer were everyone is satisfied. We all must be willing to sacrifice even though it may not be fair.”

- “If you qualify for the job you should get it without having to he hired because of your ethnicity/color. We all have the same chances at skills and education.”

- Reply: “I agree. Unfortunately, this “resolution” seems to create more “instability” than “stability”! Too much govt. Interference? What alternate resolutions were proposed?? (At least their hearts were in the right place. Where was/is yours?)” “We don’t all have the same chances. That is clearly a white privilege statement. Step outside of your world, and look at the true picture.”

- Reply: “We all have the same chances at skills and education. It isn’t our fault you don’t choose to exercise those opportunities!”

- Reply: Maybe you should step out of your box and realize that the person who wrote that may not be white; furthermore, not all white are privileged.”

- People should be judged on merit and not race. Affirmative Action has not worked and should go away.

- Reply: Most people whom are afraid of Affirmative Action don’t have the merit as it is.

- Minorities were discriminated against for 300 yrs. It has only been 40 years (not even) since the Civil Rights Bill of 1965. In the big picture that’s not much time. Continue to give minorities a leg up’ Someday we will be equal (cuz lets face it, it still isn’t even close to 100%) and Affirmative Action will not be needed.

- Reply: But racial quotas are not the answer!

- I’m for Affirmative Action since the white man has suppressed us for over 500 years.

- Reply: you oppress yourself through your ignorance

- Slavery has ended. Why must we continue to decide things based on race?

- I don’t see why I should lose a job opportunity to someone who is less qualified.

- Slavery has ended but discrimination has not

- Affirmative Action won’t go away unless close-minded business men wake up

- Race is highly over rated. Judge by merit and move on.

- Affirmative Action leads to reversed racism.

- Don’t abuse it

Table 2 – Student Responses as a Percentage of Enrollment

| Campus |

Student Enrollment |

Responses |

Response Percentage |

| Spring Creek |

10323 |

727 |

7.04% |

| Preston Ridge |

3323 |

168 |

5.06% |

| Central Park |

2546 |

133 |

5.22% |

| Total |

16192 |

1028 |

6.34% |

Table 3 – Student Responses by Topic and Campus

Campuses

|

Topics |

Spring Creek |

Preston Ridge |

Central Park |

Total |

| Abortion |

68 |

26 |

30 |

124 |

| Affirmative Action |

63 |

12 |

6 |

81 |

| Budget Cuts |

50 |

7 |

8 |

65 |

| Free Speech |

73 |

9 |

8 |

90 |

| Gay Rights |

82 |

24 |

17 |

123 |

| Gender Issues |

71 |

11 |

8 |

90 |

| Immigration |

90 |

32 |

10 |

132 |

| Racism |

112 |

20 |

11 |

143 |

| War and Peace |

71 |

19 |

21 |

111 |

| Welfare |

47 |

8 |

14 |

69 |

| Total |

727 |

168 |

133 |

1028 |

Table 4 – Student Discussion Threads by Topic and Campus

Campuses

|

Topics |

Spring Creek |

Preston Ridge |

Central Park |

Total |

| Abortion |

21 |

5 |

12 |

38 |

| Affirmative Action |

12 |

6 |

1 |

19 |

| Budget Cuts |

18 |

3 |

0 |

21 |

| Free Speech |

16 |

1 |

2 |

19 |

| Gay Rights |

20 |

12 |

2 |

34 |

| Gender Issues |

36 |

6 |

4 |

46 |

| Immigration |

27 |

15 |

4 |

46 |

| Racism |

25 |

4 |

2 |

31 |

| War and Peace |

22 |

8 |

6 |

36 |

| Welfare |

15 |

2 |

5 |

22 |

| Total |

212 |

62 |

38 |

312 |

Table 5 – Response Themes and Recommendations – Welfare

Themes:

- The population is lazy

- Single mothers

- Stereotypical view of welfare recipients

- Tax dollars

- Helps people get back on their feet

- Welfare abuse

- Welfare reform

- Provide people with help to get off welfare

- Other options

Recommendations:

- Have an individual who has been on welfare come and speak about their experience.

- Provide students with the opportunity, through the Service Learning Program, to go out in the community and visit with or help welfare recipients.

Figure 1. Evaluation of student responses as for, against, neutral or non-applicable for the topics generating the most discussion on each campus.